Innocent Until Proven Guilty.

We’re here to provide emotional and practical support for defendants.

Scroll

Disclaimer.

Our website contains information based on English and Welsh law. Although ‘The Defendant’ endeavours to ensure that the content is accurate and up to date, users should seek appropriate legal advice before taking or refraining from taking any action based on the content of this website or otherwise.

The contents of this website do not constitute legal advice and are provided for general information purposes only. If you require specific legal advice you should contact a specialist lawyer.

Select a stage

Stage 01

Investigation

Stage 02

Charged

Stage 03

Trial

Select a section

Back to stage selection

Investigation

I

Voluntary Interview

II

Arrest

III

Bail/Remand

IV

Police Investigation

V

Legal Entitlement

VI

Support

VII

Decision

VIII

Glossary

Charged

I

Legal Entitlement

II

Rights

III

Bail/Remand

IV

Support

V

Gathering of Evidence

VI

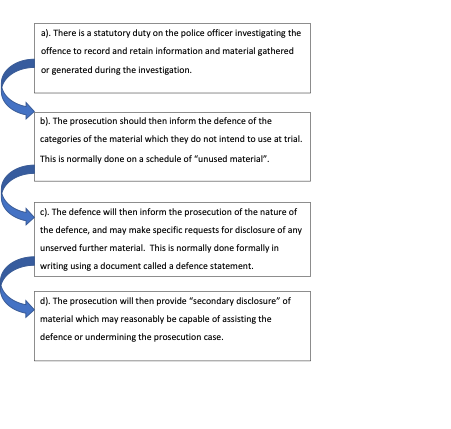

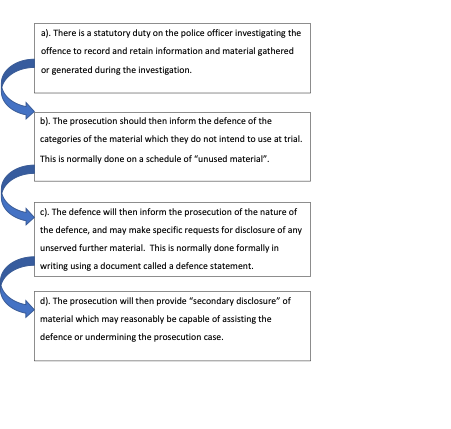

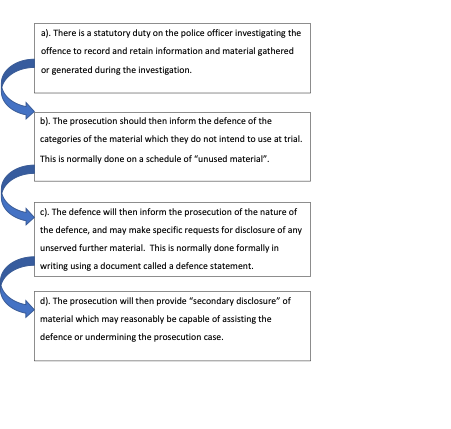

Disclosure

VII

Plea Trial

VIII

Work/Education Impact

IX

Glossary

Trial

I

Roles in a Courtroom

II

Standard Process

III

Rights

IV

Presentation of Evidence

V

Cross-examination

VI

Decision

VII

Sentencing

VIII

Appeal

IX

Glossary

Here’s the Info

Back to Group Selection

A voluntary interview is an interview requested by the police in order to assist them with an investigation, and importantly your attendance is not mandatory and requires your consent.

But the seriousness of the interview should not be overlooked simply due to its voluntary nature. During the interview you are under caution, and the interview itself is recorded and can be used as evidence in any criminal proceedings, in the situation where a decision is made to arrest you.

It is important to establish that a voluntary interview is not an arrest. They are more informal compared to the standard interviews in arrests. The police turn in favour of a voluntary interview with you if, they either do not think it is necessary to arrest you at the time, or they do not have sufficient evidence to do so.

A benefit of attending a voluntary interview is the ability to gain control over the situation. As with an interview after arrest, you would be able to consult with your solicitor, prior to the interview. And since the interview would be by appointment at a time convenient to you this would allow you more time to organise your answers, as opposed to being arrested suddenly and being underprepared for any questions asked.

If you choose not to attend your voluntary interview, you become at risk of being arrested if the police have enough evidence to do so. Therefore, it is in your best interest to attend the voluntary interview.

Prior and during your voluntary interview, you are entitled to a free solicitor to receive advice from and to be present at the interview. If you opt for a solicitor, you must communicate this to the police interviewer, who must allow you the opportunity to speak to your solicitor before interviewing you. Though a solicitor is optional, it is highly recommended as any information disclosed during the interview can be used in court against you. If you seek a solicitor, your appropriate adult can ask for one on your behalf.

Vulnerable people have the right to be assisted by an adult. This person is called your ”appropriate adult.” Your appropriate adult must be with you during the stages when the police officer informs you of your rights, as well as when the police caution is read and the officer asks you if you consent to be interviewed. You have the right to speak to your solicitor without the presence of your appropriate adult.

Your appropriate adult must also be present, if available, during the final stages of the police charging or reporting you for an offence.

You are also entitled to a right of silence, which will be communicated to you at the beginning of the interview by the police. Though, if you choose not to answer questions, it may harm your defence.

Additional rights include:

- Right to leave during the voluntary interview at any time

- Free right to an interpreter and to have documents translated

- Free right to contact your embassy for advice if you are not a British National

- Right to look at the Codes of Practice – which is a list of rules that the police will comply with during the interview

- Right to know which offence you are thought to have committed and why the police want to interview you

A voluntary interview is an interview requested by the police in order to assist them with an investigation, and importantly your attendance is not mandatory and requires your consent.

But the seriousness of the interview should not be overlooked simply due to its voluntary nature. During the interview you are under caution, and the interview itself is recorded and can be used as evidence in any criminal proceedings, in the situation where a decision is made to arrest you.

It is important to establish that a voluntary interview is not an arrest. They are more informal compared to the standard interviews in arrests. The police turn in favour of a voluntary interview with you if, they either do not think it is necessary to arrest you at the time, or they do not have sufficient evidence to do so.

A benefit of attending a voluntary interview is the ability to gain control over the situation. As with an interview after arrest, you would be able to consult with your solicitor, prior to the interview. And since the interview would be by appointment at a time convenient to you this would allow you more time to organise your answers, as opposed to being arrested suddenly and being underprepared for any questions asked.

If you choose not to attend your voluntary interview, you become at risk of being arrested if the police have enough evidence to do so. Therefore, it is in your best interest to attend the voluntary interview.

Prior and during your voluntary interview, you are entitled to a free solicitor to receive advice from and to be present at the interview. If you opt for a solicitor, you must communicate this to the police interviewer, who must allow you the opportunity to speak to your solicitor before interviewing you. Though a solicitor is optional, it is highly recommended as any information disclosed during the interview can be used in court against you. If you seek a solicitor, your appropriate adult can ask for one on your behalf.

Under 18s have the right to be assisted by an adult. This person is called your ”appropriate adult.” Your appropriate adult must be with you during the stages when the police officer informs you of your rights, as well as when the police caution is read and the officer asks you if you consent to be interviewed. You have the right to speak to your solicitor without the presence of your appropriate adult.

Your appropriate adult must also be present, if available, during the final stages of the police charging or reporting you for an offence.

You are also entitled to a right of silence, which will be communicated to you at the beginning of the interview by the police. Though, if you choose not to answer questions, it may harm your defence.

Additional rights include:

- Right to leave during the voluntary interview at any time

- Free right to an interpreter and to have documents translated

- Free right to contact your embassy for advice if you are not a British National

- Right to look at the Codes of Practice – which is a list of rules that the police will comply with during the interview

- Right to know which offence you are thought to have committed and why the police want to interview you

A voluntary interview is an interview requested by the police in order to assist them with an investigation. Importantly, it is not mandatory that you attend and such an interview requires your consent.

But the seriousness of the interview should not be overlooked simply due to its voluntary nature. During the interview you are under caution, and the interview itself is recorded and can be used as evidence in any criminal proceedings, in the situation where a decision is made to arrest you.

It is important to establish that a voluntary interview is not an arrest. They are more informal compared to the standard interviews in arrests. The police turn in favour of a voluntary interview with you if they either do not think it is necessary to arrest you at the time, or they do not have sufficient evidence to do so.

A benefit of attending a voluntary interview is the ability to gain control over the situation. As with an interview after arrest, you would be able to consult with your solicitor, prior to the interview. And since the interview would be by appointment at a time convenient to you this would allow you more time to organise your answers, as opposed to being arrested suddenly and being underprepared for any questions asked.

If you choose not to attend your voluntary interview, you become at risk of being arrested if the police have enough evidence to do so. Therefore, it is in your best interest to attend the voluntary interview.

Prior to, and during, your voluntary interview you are entitled to a free solicitor to receive advice from and to be present at the interview. If you opt for a solicitor you must communicate this to the police interviewer, who must allow you the opportunity to speak to your solicitor before interviewing you. Though a solicitor is optional, it is highly recommended as any information disclosed during the interview can be used in court against you.

You are also entitled to a right of silence, which will be communicated to you at the beginning of the interview by the police. Though, if you choose not to answer questions, it may harm your defence.

Additional rights include:

- Right to leave during the voluntary interview at any time

- Free right to an interpreter and to have documents translated

- Free right to contact your embassy for advice if you are not a British National

- Right to look at the Codes of Practice – which is a list of rules that the police will comply with during the interview

- Right to know which offence you are thought to have committed and why the police want to interview you

Anyone who is arrested should always seek legal representation even if this might involve some delay to their being interviewed/released.

An arrest is the apprehending or restraining of a person, to detain them at a police station, whilst an alleged crime is investigated. There are various things to understand if you find that you have been arrested, including: the powers of the police to arrest you, who can be arrested, on what grounds you can be arrested and your rights during and after the arrest.

The power to arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a written order which can be issued by the court. The police are able to apply to a Magistrate for a warrant to arrest a named individual, and this requires written information from the police supported by evidence which shows that the individual who has been named is suspected of committing a crime. Once this warrant has been obtained, the police have the power to arrest the individual.

The power to arrest without a warrant

The police have the power to arrest without a warrant anyone who:

- Is about to commit an offence.

- Is committing an offence.

- Is suspected to be committing an offence (on reasonable grounds).

- Is suspected to be about to commit an offence (on reasonable grounds).

The arresting officer can arrest someone only if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary for one of the following reasons:

- To find out the person’s name and address.

- To stop them causing physical injury to themselves or others

- To stop them from suffering injury.

- To stop them damaging property.

- To stop them committing an offence against public decency.

- To prevent causing an unlawful obstruction of the highway.

- To protect a child or another vulnerable person.

- To allow a quick and effective investigation of an offence.

- To prevent the person from disappearing and hindering any prosecution of an offence.

So, what are reasonable grounds?

Having ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing something means that the arresting officer has an honest belief based on facts or evidence that would lead an ordinary person to conclude that the person who had been arrested was guilty of an offence.

What does a lawful arrest require?

Two things:

- A person’s suspected or attempted involvement in an offence.

- Reasonable grounds for believing that the arrest is necessary.

During the arrest, the police officer must also tell you that you are under arrest and the grounds for your arrest, which must be explained to you in simple and non-technical language.

Police officers are also permitted to use reasonable force when carrying out an arrest. This means that any force they use must be reasonable in the circumstances, and not excessive. They also retain the right to search an arrested person. They can do this for 3 reasons:

- If they have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may present a danger to themselves or others.

- To search for anything they might use to assist them to escape custody.

- To search for any evidence relating to an offence.

Powers of Detention

Once you are arrested, you must be taken to a designated police station, with a custody officer. Custody officers are experienced officers who are not a part of the investigation team on the offence you’ve been arrested for. They are responsible for those in detention and for keeping records; it is their job to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge you, and their job to detain you, and to release you if they do not have sufficient evidence to charge you.

If they have reasonable grounds to believe that it’s necessary to detain you while they obtain evidence relating to the offence you’ve been arrested for, they can authorise keeping you in police detention.

Where they allow you to be kept in police detention without being charged, they must write up a written record of grounds for your detention, as soon as possible, and they should do this in your presence, explaining the grounds, unless –

- You are incapable of understanding what is said at the time.

- You are violent, or likely to become violent.

- You are in need of medical treatment.

Time Limits on Detention

Detention begins when you arrive at the station after arrest and the custody officer declares there is a reason for detention. After this, there must be a review after 6 hours, then 15 hours, and every 9 hours thereafter.

The general rule is that the police may detain someone for 24 hours. They can detain for a further 12 hours (36 hours total) with permission of a senior officer, but only if you are under arrest for an indictable offence (this is a more serious offence, that can only be tried in the Crown Court). For indictable offences, you can be detained beyond 36 hours, but only if the police apply to the Magistrates’ Court. They can allow detention of up to 96 hours, but this must be done in two applications to the Magistrates’ Court – the first can permit a further 36 hours detention (72 hours total) and 24 hours upon second application (96 hours total).

Anyone who is arrested should always seek legal representation even if this might involve some delay to their being interviewed/released.

An arrest is the apprehending or restraining of a person, to detain them at a police station, whilst an alleged crime is investigated. There are various things to understand if you find that you have been arrested, including: the powers of the police to arrest you, who can be arrested, on what grounds you can be arrested and your rights during and after the arrest.

The power to arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a written order which can be issued by the court. The police are able to apply to a Magistrate for a warrant to arrest a named individual, and this requires written information from the police supported by evidence which shows that the individual who has been named is suspected of committing a crime. Once this warrant has been obtained, the police have the power to arrest the individual.

The power to arrest without a warrant

The police have the power to arrest without a warrant anyone who:

- Is about to commit an offence.

- Is committing an offence.

- Is suspected to be committing an offence (on reasonable grounds).

- Is suspected to be about to commit an offence (on reasonable grounds).

The arresting officer can arrest someone only if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary for one of the following reasons:

- To find out the person’s name and address.

- To stop them causing physical injury to themselves or others

- To stop them from suffering injury.

- To stop them damaging property.

- To stop them committing an offence against public decency.

- To prevent causing an unlawful obstruction of the highway.

- To protect a child or another vulnerable person.

- To allow a quick and effective investigation of an offence.

- To prevent the person from disappearing and hindering any prosecution of an offence.

So, what are reasonable grounds?

Having ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing something means that the arresting officer has an honest belief based on facts or evidence that would lead an ordinary person to conclude that the person who had been arrested was guilty of an offence.

What does a lawful arrest require?

Two things:

- A person’s suspected or attempted involvement in an offence.

- Reasonable grounds for believing that the arrest is necessary.

During the arrest, the police officer must also tell you that you are under arrest and the grounds for your arrest, which must be explained to you in simple and non-technical language.

Police officers are also permitted to use reasonable force when carrying out an arrest. This means that any force they use must be reasonable in the circumstances, and not excessive. They also retain the right to search an arrested person. They can do this for 3 reasons:

- If they have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may present a danger to themselves or others.

- To search for anything they might use to assist them to escape custody.

- To search for any evidence relating to an offence.

Powers of Detention

Once you are arrested, you must be taken to a designated police station, with a custody officer. Custody officers are experienced officers who are not a part of the investigation team on the offence you’ve been arrested for. They are responsible for those in detention and for keeping records; it is their job to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge you, and their job to detain you, and to release you if they do not have sufficient evidence to charge you.

If they have reasonable grounds to believe that it’s necessary to detain you while they obtain evidence relating to the offence you’ve been arrested for, they can authorise keeping you in police detention.

Where they allow you to be kept in police detention without being charged, they must write up a written record of grounds for your detention, as soon as possible, and they should do this in your presence, explaining the grounds, unless –

- You are incapable of understanding what is said at the time.

- You are violent, or likely to become violent.

- You are in need of medical treatment.

Time Limits on Detention

Detention begins when you arrive at the station after arrest and the custody officer declares there is a reason for detention. After this, there must be a review after 6 hours, then 15 hours, and every 9 hours thereafter.

The general rule is that the police may detain someone for 24 hours. They can detain for a further 12 hours (36 hours total) with permission of a senior officer, but only if you are under arrest for an indictable offence (this is a more serious offence, that can only be tried in the Crown Court). For indictable offences, you can be detained beyond 36 hours, but only if the police apply to the Magistrates’ Court. They can allow detention of up to 96 hours, but this must be done in two applications to the Magistrates’ Court – the first can permit a further 36 hours detention (72 hours total) and 24 hours upon second application (96 hours total).

Anyone who is arrested should always seek legal representation even if this might involve some delay to their being interviewed/released.

An arrest is the apprehending or restraining of a person, to detain them at a police station, whilst an alleged crime is investigated. There are various things to understand if you find that you have been arrested, including: the powers of the police to arrest you, who can be arrested, on what grounds you can be arrested and your rights during and after the arrest.

The power to arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a written order which can be issued by the court. The police are able to apply to a Magistrate for a warrant to arrest a named individual, and this requires written information from the police supported by evidence which shows that the individual who has been named is suspected of committing a crime. Once this warrant has been obtained, the police have the power to arrest the individual.

The power to arrest without a warrant

The police have the power to arrest without a warrant anyone who:

- Is about to commit an offence.

- Is committing an offence.

- Is suspected to be committing an offence (on reasonable grounds).

- Is suspected to be about to commit an offence (on reasonable grounds).

The arresting officer can arrest someone only if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary for one of the following reasons:

- To find out the person’s name and address.

- To stop them causing physical injury to themselves or others

- To stop them from suffering injury.

- To stop them damaging property.

- To stop them committing an offence against public decency.

- To prevent causing an unlawful obstruction of the highway.

- To protect a child or another vulnerable person.

- To allow a quick and effective investigation of an offence.

- To prevent the person from disappearing and hindering any prosecution of an offence.

So, what are reasonable grounds?

Having ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing something means that the arresting officer has an honest belief based on facts or evidence that would lead an ordinary person to conclude that the person who had been arrested was guilty of an offence.

What does a lawful arrest require?

Two things:

- A person’s suspected or attempted involvement in an offence.

- Reasonable grounds for believing that the arrest is necessary.

During the arrest, the police officer must also tell you that you are under arrest and the grounds for your arrest, which must be explained to you in simple and non-technical language.

Police officers are also permitted to use reasonable force when carrying out an arrest. This means that any force they use must be reasonable in the circumstances, and not excessive. They also retain the right to search an arrested person. They can do this for 3 reasons:

- If they have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may present a danger to themselves or others.

- To search for anything they might use to assist them to escape custody.

- To search for any evidence relating to an offence.

Powers of Detention

Once you are arrested, you must be taken to a designated police station, with a custody officer. Custody officers are experienced officers who are not a part of the investigation team on the offence you’ve been arrested for. They are responsible for those in detention and for keeping records; it is their job to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge you, and their job to detain you, and to release you if they do not have sufficient evidence to charge you.

If they have reasonable grounds to believe that it’s necessary to detain you while they obtain evidence relating to the offence you’ve been arrested for, they can authorise keeping you in police detention.

Where they allow you to be kept in police detention without being charged, they must write up a written record of grounds for your detention, as soon as possible, and they should do this in your presence, explaining the grounds, unless –

- You are incapable of understanding what is said at the time.

- You are violent, or likely to become violent.

- You are in need of medical treatment.

Time Limits on Detention

Detention begins when you arrive at the station after arrest and the custody officer declares there is a reason for detention. After this, there must be a review after 6 hours, then 15 hours, and every 9 hours thereafter.

The general rule is that the police may detain someone for 24 hours. They can detain for a further 12 hours (36 hours total) with permission of a senior officer, but only if you are under arrest for an indictable offence (this is a more serious offence, that can only be tried in the Crown Court). For indictable offences, you can be detained beyond 36 hours, but only if the police apply to the Magistrates’ Court. They can allow detention of up to 96 hours, but this must be done in two applications to the Magistrates’ Court – the first can permit a further 36 hours detention (72 hours total) and 24 hours upon second application (96 hours total).

Anyone who is arrested should always seek legal representation even if this might involve some delay to their being interviewed/released.

An arrest is the apprehending or restraining of a person, to detain them at a police station, whilst an alleged crime is investigated. There are various things to understand if you find that you have been arrested, including: the powers of the police to arrest you, who can be arrested, on what grounds you can be arrested and your rights during and after the arrest.

The power to arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a written order which can be issued by the court. The police are able to apply to a Magistrate for a warrant to arrest a named individual, and this requires written information from the police supported by evidence which shows that the individual who has been named is suspected of committing a crime. Once this warrant has been obtained, the police have the power to arrest the individual.

The power to arrest without a warrant

The police have the power to arrest without a warrant anyone who:

- Is about to commit an offence.

- Is committing an offence.

- Is suspected to be committing an offence (on reasonable grounds).

- Is suspected to be about to commit an offence (on reasonable grounds).

The arresting officer can arrest someone only if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary for one of the following reasons:

- To find out the person’s name and address.

- To stop them causing physical injury to themselves or others

- To stop them from suffering injury.

- To stop them damaging property.

- To stop them committing an offence against public decency.

- To prevent causing an unlawful obstruction of the highway.

- To protect a child or another vulnerable person.

- To allow a quick and effective investigation of an offence.

- To prevent the person from disappearing and hindering any prosecution of an offence.

So, what are reasonable grounds?

Having ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing something means that the arresting officer has an honest belief based on facts or evidence that would lead an ordinary person to conclude that the person who had been arrested was guilty of an offence.

What does a lawful arrest require?

Two things:

- A person’s suspected or attempted involvement in an offence.

- Reasonable grounds for believing that the arrest is necessary.

During the arrest, the police officer must also tell you that you are under arrest and the grounds for your arrest, which must be explained to you in simple and non-technical language.

Police officers are also permitted to use reasonable force when carrying out an arrest. This means that any force they use must be reasonable in the circumstances, and not excessive. They also retain the right to search an arrested person. They can do this for 3 reasons:

- If they have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may present a danger to themselves or others.

- To search for anything they might use to assist them to escape custody.

- To search for any evidence relating to an offence.

Powers of Detention

Once you are arrested, you must be taken to a designated police station, with a custody officer. Custody officers are experienced officers who are not a part of the investigation team on the offence you’ve been arrested for. They are responsible for those in detention and for keeping records; it is their job to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge you, and their job to detain you, and to release you if they do not have sufficient evidence to charge you.

If they have reasonable grounds to believe that it’s necessary to detain you while they obtain evidence relating to the offence you’ve been arrested for, they can authorise keeping you in police detention.

Where they allow you to be kept in police detention without being charged, they must write up a written record of grounds for your detention, as soon as possible, and they should do this in your presence, explaining the grounds, unless –

- You are incapable of understanding what is said at the time.

- You are violent, or likely to become violent.

- You are in need of medical treatment.

Time Limits on Detention

Detention begins when you arrive at the station after arrest and the custody officer declares there is a reason for detention. After this, there must be a review after 6 hours, then 15 hours, and every 9 hours thereafter.

The general rule is that the police may detain someone for 24 hours. They can detain for a further 12 hours (36 hours total) with permission of a senior officer, but only if you are under arrest for an indictable offence (this is a more serious offence, that can only be tried in the Crown Court). For indictable offences, you can be detained beyond 36 hours, but only if the police apply to the Magistrates’ Court. They can allow detention of up to 96 hours, but this must be done in two applications to the Magistrates’ Court – the first can permit a further 36 hours detention (72 hours total) and 24 hours upon second application (96 hours total).

Anyone who is arrested should always seek legal representation even if this might involve some delay to their being interviewed/released.

An arrest is the apprehending or restraining of a person, to detain them at a police station, whilst an alleged crime is investigated. There are various things to understand if you find that you have been arrested, including: the powers of the police to arrest you, who can be arrested, on what grounds you can be arrested and your rights during and after the arrest.

The power to arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a written order which can be issued by the court. The police are able to apply to a Magistrate for a warrant to arrest a named individual, and this requires written information from the police supported by evidence which shows that the individual who has been named is suspected of committing a crime. Once this warrant has been obtained, the police have the power to arrest the individual.

The power to arrest without a warrant

The police have the power to arrest without a warrant anyone who:

- Is about to commit an offence.

- Is committing an offence.

- Is suspected to be committing an offence (on reasonable grounds).

- Is suspected to be about to commit an offence (on reasonable grounds).

The arresting officer can arrest someone only if he has reasonable grounds for believing that it is necessary for one of the following reasons:

- To find out the person’s name and address.

- To stop them causing physical injury to themselves or others

- To stop them from suffering injury.

- To stop them damaging property.

- To stop them committing an offence against public decency.

- To prevent causing an unlawful obstruction of the highway.

- To protect a child or another vulnerable person.

- To allow a quick and effective investigation of an offence.

- To prevent the person from disappearing and hindering any prosecution of an offence.

So, what are reasonable grounds?

Having ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing something means that the arresting officer has an honest belief based on facts or evidence that would lead an ordinary person to conclude that the person who had been arrested was guilty of an offence.

What does a lawful arrest require?

Two things:

- A person’s suspected or attempted involvement in an offence.

- Reasonable grounds for believing that the arrest is necessary.

During the arrest, the police officer must also tell you that you are under arrest and the grounds for your arrest, which must be explained to you in simple and non-technical language.

Police officers are also permitted to use reasonable force when carrying out an arrest. This means that any force they use must be reasonable in the circumstances, and not excessive. They also retain the right to search an arrested person. They can do this for 3 reasons:

- If they have reasonable grounds for believing that the person may present a danger to themselves or others.

- To search for anything they might use to assist them to escape custody.

- To search for any evidence relating to an offence.

Powers of Detention

Once you are arrested, you must be taken to a designated police station, with a custody officer. Custody officers are experienced officers who are not a part of the investigation team on the offence you’ve been arrested for. They are responsible for those in detention and for keeping records; it is their job to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to charge you, and their job to detain you, and to release you if they do not have sufficient evidence to charge you.

If they have reasonable grounds to believe that it’s necessary to detain you while they obtain evidence relating to the offence you’ve been arrested for, they can authorise keeping you in police detention.

Where they allow you to be kept in police detention without being charged, they must write up a written record of grounds for your detention, as soon as possible, and they should do this in your presence, explaining the grounds, unless –

- You are incapable of understanding what is said at the time.

- You are violent, or likely to become violent.

- You are in need of medical treatment.

Time Limits on Detention

Detention begins when you arrive at the station after arrest and the custody officer declares there is a reason for detention. After this, there must be a review after 6 hours, then 15 hours, and every 9 hours thereafter.

The general rule is that the police may detain someone for 24 hours. They can detain for a further 12 hours (36 hours total) with permission of a senior officer, but only if you are under arrest for an indictable offence (this is a more serious offence, that can only be tried in the Crown Court such as rape, robbery or some serious assaults).

For indictable offences, you can be detained beyond 36 hours, but only if the police apply to the Magistrates’ Court. They can allow detention of up to 96 hours, but this must be done in two applications to the Magistrates’ Court – the first can permit a further 36 hours detention (72 hours total) and 24 hours upon second application (96 hours total).

Right to have someone informed

You have the right to have someone informed of your detention, as soon as is practicable. This extends to one friend, relative or another person who is likely to take an interest in your welfare. The police will normally ask for 3-4 names and numbers in order to fulfil this obligation, but only one will be informed.

If you are detained in connection with an indictable offence, a senior police officer may delay informing someone for up to 36 hours. However, they can only do this if they have reasonable grounds to believe that telling the person will –

- Interfere with or harm evidence

- Interfere with or harm other people

- Alert others involved in the offence, or

- Slow down the recovery of property obtained through the offence.

Making a telephone call

You may also be allowed to speak on the phone to one person, for a reasonable time. This is in addition to the right to have someone informed of the arrest. Unless the call is to a solicitor, a police officer can listen to the call and is allowed to terminate it if they believe it is being abused.

You must be warned and should be aware if there is anything you say in a call, to anyone other than your solicitor, it can be given in evidence, and that this is not an absolute right – it can be refused or delayed by the police.

Right to legal advice

You can either contact your own solicitor if you have one or use the duty solicitors provided for free for anyone under arrest.

If you are suspected of committing an indictable offence, an officer of superintendent rank or above might delay informing someone for up to 36 hours, if they have reasonable grounds for believing that not doing this will –

- Lead to interference with, or harm to, evidence connected to the offence.

- Lead to interference with, or harm to, other people.

- Lead to serious loss of, or damage to, property.

- Lead to alerting other people suspected of having committed an offence but not yet arrested for it.

Delaying the right to legal advice can only be justified on rare occasions though, and the decision must be based on specific aspects of the case, not just a general assumption that access to a solicitor might lead to the alerting of accomplices.

The police are allowed to start questioning before the solicitor arrives if the matter is urgent, or the solicitor is likely to be delayed for some time. You are also allowed to consult the police Code of Practice which sets out police rules relating to detention.

Cell conditions

Cells must be adequately heated, lit, cleaned and ventilated. You are allowed at least two light meals and one main meal in any 24-hour period. Drinks should be provided at mealtimes and upon reasonable requests between meals. You must also be allowed eight hours continuous rest in a 24-hour period.

Your rights during interview

All interviews at a police station have to be tape-recorded (in accordance with PACE Code E) and in some cases (determined by Code F), the interview must be video recorded. Video recordings are more likely to be considered where –

- You or your solicitor or appropriate adult requests for the interview to be visually recorded.

- You or someone else present is deaf or deaf/blind or speech impaired and uses sign language.

- The interviewer suspects that you might demonstrate your actions or behaviour at the time or to examine a particular item or object handed to you.

- The authorised recording device used in accordance with Code E incorporates a camera and creates a combined audio and visual recording and does not allow the visual recording function to operate independently of the audio recording function.

The interview rooms must be adequately heated, lit and ventilated. Breaks should take place at recognised mealtimes and there should be a short refreshment break every two hours. You can only be interviewed under caution – you have to be warned of your right to silence, but that if you don’t answer questions it can go against your case.

Pace Codes of Practice

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/police-and-criminal-evidence-act-1984-pace-codes-of-practice (Please check that these codes are up-to-date at the time of viewing)

Treatment of suspects and exclusion of evidence

The court has power to prevent the prosecution using statements which have been obtained through oppression to be used as evidence which includes lies, manipulation or abuse of power.

Right to Silence

You can refuse to answer any questions asked during your interviews, but the law allows inferences to be drawn from the fact that a suspect has refused to answer questions. If your case goes to trial, the judge can comment on your failure to mention a crucial matter and this can form part of the evidence against you at trial.

Strip searches

The custody officer must check the property you have with you. This means that you might be searched if the officer thinks this is necessary to carry out his/her duty to the extent that the custody officer considers necessary.

Clothes and personal effects may only be seized if the custody officer believes that you might use them –

- To cause physical injury to yourself or someone else.

- To damage property

- To interfere with evidence

- To assist you to escape

- Or that it may be evidence relating to an offence.

This involves the removal of more than outer clothing, including shoes and socks. This is only allowed if it’s necessary to remove something you should not be allowed to keep and there is a reasonable suspicion that the suspect might have concealed such an article.

The search must be conducted by a member of the same sex in a place where it cannot be seen by anyone who does not need to be present. You should not normally be required to remove all clothing at the same time.

Intimate searches

This consists of the physical examination of a person’s body orifices other than the mouth. This can only be authorised by a high-ranking officer if there are reasonable grounds to believe you might have concealed an item which could be used to cause injury to yourself or others or, that you’re in possession of a Class A drug, and this is the only means of removing the item.

Two people must be present in addition to you. Where drugs are concerned, the search must be carried out by a suitably qualified person such as a doctor or nurse at medical premises. Other searches can be conducted by a same sex constable, if an Inspector authorises it, but only as a last resort.

Fingerprints and body samples

Fingerprints can be taken by the police at the police station. They will ask you to agree to this, but if you do not consent the police can use reasonable force to take fingerprints.

“Intimate samples” may include dental impressions, samples of blood, semen or any other tissue fluid, urine or pubic hair, or a swab taken from any part of your genitals or from a body orifice other than the mouth. They can be taken if –

- A police officer of Inspector rank or above has reasonable grounds to believe such an impression or sample will confirm or disprove the suspect’s involvement in a recordable offence and gives authorisation for a sample to be taken.

- With your written consent

- You must be informed of the reason, including the nature of the suspected offence.

- You must also be informed that authorisation has been given, and a sample taken at the police station may be subject of a speculative search. You must also be warned that if you refuse without good cause, this refusal may harm your case if it comes to trial.

Non-intimate samples may be taken without consent and reasonable force may be used. These include samples of hair, other than pubic hair, which includes hair plucked from the root, a sample taken from a nail or from under a nail, a swab taken from any part of a person’s body other than a part from which an intimate swab would be taken, or saliva.

Bail – Where a person is released by the Police, Magistrates’ Court or Crown Court after being charged with an offence and is allowed to go home whilst awaiting his trial.

However, in some cases, conditions may be imposed upon a person’s bail.

Remand – Where a person is placed into custody (e.g. a prison or detention centre) once he has been charged with an offence. The person will remain in custody until the hearing at the Magistrates’ court. At the hearing, the Magistrates may decide that the person shall remain in custody until his trial date or may be granted bail (which may be subject to conditions) until his trial date.

If the police are not yet in a position to charge a suspect and can no longer detain the suspect for questioning, the suspect must be released. The police may release the suspect either on bail (this may be subject to conditions and the police have certain powers of arrest where such conditions have been breached) or without bail to investigate further on the matter.

If the police release the suspect on bail, they can only allow that person to be on bail for a maximum of 28 days (however, in rare circumstances, this may be extended). Within this 28-day period, the police will carry out further enquiries and obtain a decision as to whether the suspect should be charged or not.

Generally, everyone has a right to bail but this general right will not apply where a person is charged with Murder, Manslaughter, a Serious Sexual Offence or is a Class A Drug User (if any of these charges apply, bail will only be granted if there are exceptional circumstances to justify it).

There may be other situations where bail is unlikely to be granted. For example, if someone is charged with a serious crime not listed above (i.e. armed robbery), if they have past convictions for serious crimes, if they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or if the police have reason to believe that the person may commit a crime whilst on bail or will not turn up for their hearing.

Bail can be given unconditionally (without conditions). This means that there are no rules attached to it and the person given bail does not need to comply with any specific requirements.

Alternatively, a person may be given conditional bail which means they will need to follow certain rules (See relevant section below for more information).

If someone is given conditional bail, they may need to follow certain rules, for example:

– Reporting to the Police station at regular agreed times.

– Not driving whilst on bail

– Not contacting certain people

– Notifying the prosecutor of the address that they staying at

– Adhering to a curfew (this may be checked by electronic monitoring)

– Agreeing to electronic monitoring with a GPS Location tracker

– Making a payment

– Surrendering a document or item

– Giving a security (ie. giving an item such as a passport to the courts or police – this item will be returned to you at the end of your bail).

Breach of conditions for bail – where a person has broken one or more condition(s) of their bail then there may be consequences.

A police officer has the power to arrest a person if he has reasonable grounds to believe that the person on bail is likely to break one of the bail conditions or if the person has already broken one of these conditions.

Once the person has been arrested, that person must be brought before the Magistrates’ court and be dealt with within 24 hours of the arrest.

Consequently, the Magistrates’ Court may decide to place that person in remand (custody) or may grant him bail, subject to the same or different conditions as before.

A person charged with an offence may be placed in remand if:

– They are charged with a serious crime,

– If they have been convicted in the past for a serious crime,

– If the police believe that the person on bail will not attend the court hearing,

– If they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or

– If the police have reason to believe that they may commit a crime whilst on bail.

If a person is put on remand before the trial takes place, the individual has not been convicted of the crime but merely placed in custody until the trial. This means that they should not be treated as a prisoner and will have certain rights such as wearing their own clothes, having more frequent visits etc.

Bail – Where a person is released by the Police, Magistrates’ Court or Crown Court after being charged with an offence and is allowed to go home whilst awaiting his trial.

However, in some cases, conditions may be imposed upon a person’s bail.

Remand – Where a person is placed into custody once he has been charged with an offence. Individuals under 18 who are placed on remand will be taken to a secure centre for young people and not be placed in an adult prison. The person will remain in custody until the hearing at the Magistrates’ court. At the hearing, the Magistrates may decide that the person shall remain in custody until his trial date or may be granted bail (which may be subject to conditions) until his trial date.

If the police are not yet in a position to charge a suspect and can no longer detain the suspect for questioning, the suspect must be released. The police may release the suspect either on bail (this may be subject to conditions and the police have certain powers of arrest where such conditions have been breached) or without bail to investigate further on the matter.

If the police release the suspect on bail, they can only allow that person to be on bail for a maximum of 28 days (however, in rare circumstances, this may be extended). Within this 28-day period, the police will carry out further enquiries and obtain a decision as to whether the suspect should be charged or not.

Generally, everyone has a right to bail but this general right will not apply where a person is charged with Murder, Manslaughter, a Serious Sexual Offence or is a Class A Drug User (if any of these charges apply, bail will only be granted if there are exceptional circumstances to justify it).

There may be other situations where bail is unlikely to be granted. For example, if someone is charged with a serious crime not listed above (i.e. armed robbery), if they have past convictions for serious crimes, if they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or if the police have reason to believe that the person may commit a crime whilst on bail or will not turn up for their hearing.

Bail can be given unconditionally (without conditions). This means that there are no rules attached to it and the person given bail does not need to comply with any specific requirements.

Alternatively, a person may be given conditional bail which means they will need to follow certain rules (See relevant section below for more information).

If someone is given conditional bail, they may need to follow certain rules, for example:

– Reporting to the Police station at regular agreed times.

– Not driving whilst on bail

– Not contacting certain people

– Notifying the prosecutor of the address that they staying at

– Adhering to a curfew (this may be checked by electronic monitoring)

– Agreeing to electronic monitoring with a GPS Location tracker

– Making a payment

– Surrendering a document or item

– Giving a security (ie. giving an item such as a passport to the courts or police – this item will be returned to you at the end of your bail).

- They may also be subject to the condition that they must attend and participate in bail support, bail support and supervision as well as Intensive and Surveillance (ISS) Programme.

Bail conditions for under 18’s:

- Youths may be subject to similar conditions as adults (see above). They may also be subject to the condition that they must attend and participate in bail support, bail support and supervision as well as Intensive and Surveillance (ISS) Programme.

Breach of conditions for bail – where a person has broken one or more condition(s) of their bail then there may be consequences.

A police officer has the power to arrest a person if he has reasonable grounds to believe that the person on bail is likely to break one of the bail conditions or if the person has already broken one of these conditions.

Once the person has been arrested, that person must be brought before the Magistrates’ court and be dealt with within 24 hours of the arrest.

Consequently, the Magistrates’ Court may decide to place that person in remand (custody) or may grant him bail, subject to the same or different conditions as before.

A person charged with an offence may be placed in remand if:

– They are charged with a serious crime,

– If they have been convicted in the past for a serious crime,

– If the police believe that the person on bail will not attend the court hearing,

– If they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or

– If the police have reason to believe that they may commit a crime whilst on bail.

If a person is put on remand before the trial takes place, the individual has not been convicted of the crime but merely placed in custody until the trial. This means that they should not be treated as a prisoner and will have certain rights such as wearing their own clothes, having more frequent visits etc.

Bail – Where a person is released by the Police, Magistrates’ Court or Crown Court after being charged with an offence and is allowed to go home whilst awaiting his trial.

However, in some cases, conditions may be imposed upon a person’s bail.

Remand – Where a person is placed into custody (e.g. a prison or detention centre) once he has been charged with an offence. The person will remain in custody until the hearing at the Magistrates’ court. At the hearing, the Magistrates may decide that the person shall remain in custody until his trial date or may be granted bail (which may be subject to conditions) until his trial date.

If the police are not yet in a position to charge a suspect and can no longer detain the suspect for questioning, the suspect must be released. The police may release the suspect either on bail (this may be subject to conditions and the police have certain powers of arrest where such conditions have been breached) or without bail to investigate further on the matter.

If the police release the suspect on bail, they can only allow that person to be on bail for a maximum of 28 days (however, in rare circumstances, this may be extended). Within this 28-day period, the police will carry out further enquiries and obtain a decision as to whether the suspect should be charged or not.

Generally, everyone has a right to bail but this general right will not apply where a person is charged with Murder, Manslaughter, a Serious Sexual Offence or is a Class A Drug User (if any of these charges apply, bail will only be granted if there are exceptional circumstances to justify it).

There may be other situations where bail is unlikely to be granted. For example, if someone is charged with a serious crime not listed above (i.e. armed robbery), if they have past convictions for serious crimes, if they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or if the police have reason to believe that the person may commit a crime whilst on bail or will not turn up for their hearing.

Bail can be given unconditionally (without conditions). This means that there are no rules attached to it and the person given bail does not need to comply with any specific requirements.

Alternatively, a person may be given conditional bail which means they will need to follow certain rules (See relevant section below for more information).

If someone is given conditional bail, they may need to follow certain rules, for example:

– Reporting to the Police station at regular agreed times.

– Not driving whilst on bail

– Not contacting certain people

– Notifying the prosecutor of the address that they staying at

– Adhering to a curfew (this may be checked by electronic monitoring)

– Agreeing to electronic monitoring with a GPS Location tracker

– Making a payment

– Surrendering a document or item

– Giving a security (ie. giving an item such as a passport to the courts or police – this item will be returned to you at the end of your bail).

Breach of conditions for bail – where a person has broken one or more condition(s) of their bail then there may be consequences.

A police officer has the power to arrest a person if he has reasonable grounds to believe that the person on bail is likely to break one of the bail conditions or if the person has already broken one of these conditions.

Once the person has been arrested, that person must be brought before the Magistrates’ court and be dealt with within 24 hours of the arrest.

Consequently, the Magistrates’ Court may decide to place that person in remand (custody) or may grant him bail, subject to the same or different conditions as before.

A person charged with an offence may be placed in remand if:

– They are charged with a serious crime,

– If they have been convicted in the past for a serious crime,

– If the police believe that the person on bail will not attend the court hearing,

– If they have previously been given bail but breached the conditions or

– If the police have reason to believe that they may commit a crime whilst on bail.

If a person is put on remand before the trial takes place, the individual has not been convicted of the crime but merely placed in custody until the trial. This means that they should not be treated as a prisoner and will have certain rights such as wearing their own clothes, having more frequent visits etc.

Suspects will generally become aware of in investigation taking place if the police ask to question them, or the suspect is arrested, searched or held in police custody.

If a person is interviewed or arrested, they may then be released under investigation or released on bail.

Subsequently there is no time frame for how long an investigation may take, if the investigation is straight forward then it may take just a few hours. However more complex cases may take years.

The police will try and keep suspects updated at important points in the investigation and will contact suspects at the end of an investigation.

Suspects are often asked to provide significant amounts of information to the police, this may include access to their mobile phones, medical records and financial evidence.

The police are responsible for the investigation and it is their duty to investigate aspects that they believe to be important. Once the police have decided that they have enough evidence from the investigation, they will refer their findings to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Police may decide straight away that they do not wish to proceed further with the suspect.

Sometimes, if the police need more information then suspects will be released under investigation or released on bail.

If a suspect is released under investigation, then this means the police are continuing their investigation but there is no need for a suspect to return to the police station, and there are no other conditions attached. Suspects will wait for the police to contact them with more information.

If a suspect is charged with an offence, then they will be given a court date to attend. Being charged with an offence does not mean a suspect has been convicted, further action can be taken if the suspect pleads not guilty leading to a formal investigation and court trial.

Suspects will generally become aware of in investigation taking place if the police ask to question them, or the suspect is arrested, searched or held in police custody.

If a person is interviewed or arrested, they may then be released under investigation or released on bail.

Subsequently there is no time frame for how long an investigation may take, if the investigation is straight forward then it may take just a few hours. However more complex cases may take years.

The police will try and keep suspects updated at important points in the investigation and will contact suspects at the end of an investigation.

Suspects are often asked to provide significant amounts of information to the police, this may include access to their mobile phones, medical records and financial evidence.

The police are responsible for the investigation and it is their duty to investigate aspects that they believe to be important. Once the police have decided that they have enough evidence from the investigation, they will refer their findings to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Police may decide straight away that they do not wish to proceed further with the suspect.

Sometimes, if the police need more information then suspects will be released under investigation or released on bail.

If a suspect is released under investigation, then this means the police are continuing their investigation but there is no need for a suspect to return to the police station, and there are no other conditions attached. Suspects will wait for the police to contact them with more information.

If a suspect is released under police bail this means that the suspect has an obligation to return to the police station at a specified time and date. Conditions may also be placed on suspects, for example curfews to abide by may be given. If bail is breached by either not turning up to the police station or violating conditions, then the police can arrest the suspect and bring them to court. In some instances, a suspect may be sent to prison.

If a suspect is charged with an offence, then they will be given a court date to attend. Being charged with an offence does not mean a suspect has been convicted, further action can be taken if the suspect pleads not guilty leading to a formal investigation and court trial.

Suspects will generally become aware of in investigation taking place if the police ask to question them, or the suspect is arrested, searched or held in police custody.

If a person is interviewed or arrested, they may then be released under investigation or released on bail.

Subsequently there is no time frame for how long an investigation may take, if the investigation is straight forward then it may take just a few hours. However more complex cases may take years.

The police will try and keep suspects updated at important points in the investigation and will contact suspects at the end of an investigation.

Suspects are often asked to provide significant amounts of information to the police, this may include access to their mobile phones, medical records and financial evidence.

The police are responsible for the investigation and it is their duty to investigate aspects that they believe to be important. Once the police have decided that they have enough evidence from the investigation, they will refer their findings to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Police may decide straight away that they do not wish to proceed further with the suspect.

Sometimes, if the police need more information then suspects will be released under investigation or released on bail.

If a suspect is released under investigation, then this means the police are continuing their investigation but there is no need for a suspect to return to the police station, or any other conditions attached. Suspects will wait for the police to contact them with more information.

If a suspect is released under police bail this means that the suspect has an obligation to return to the police station at a specified time and date. Conditions may also be placed on suspects, for example curfews to abide by may be given. If bail is breached by either not turning up to the police station or violating conditions, then the police can arrest the suspect and bring them to court. In some instances, a suspect may be sent to prison.

If a suspect is charged with an offence, then they will be given a court date to attend. Being charged with an offence does not mean a suspect has been convicted, further action can be taken if the suspect pleads not guilty leading to a formal investigation and court trial.

Criminal Law – Legal Process Glossary

This glossary applies to England and Wales. The information here is based on information available on the Crown Prosecution Service website, The Law Society website, and the website of the Courts and Tribunals Judiciary.

Accused – To be charged with an offence.

Advocate – The lawyer who represents a person, or persons, in court.

Allegation – A claim that someone has acted unlawfully, or a claim made against someone (usually without proof).

Appeal – When a person is unhappy with a judgment and seeks to change it – this could be an appeal against a conviction or sentence. Sometimes, permission (referred to as ‘leave’) to appeal is required to appeal. Proper grounds for appeal are always required.

Barrister – A lawyer who is specialised in representing people in court, drafting pleadings, and offering expert legal opinions.

Bail – When a person who is charged with an offence is allowed to stay at home and be in the community while awaiting the court trial of their case.

Client – A person who uses the services of a lawyer or other legal professional.

Convicted – To be found guilty of a crime.

Counsel – Another word for barrister.

Cross-Examination – When a barrister asks questions to a witness in front of a judge and jury in court.

Crown Advocate – Crown Advocates review and prepare cases. They decide on trial tactics and provide pre-charge advice, and sometimes they present cases in court.

Crown Court – The court for serious crimes. If a defendant pleads not guilty of a serious crime, their case is heard in the Crown Court in front of a judge, and jury of 12 people. The jury decides whether a defendant is guilty or innocent.

Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) – The organisation that prosecutes criminal cases investigated by the police of England and Wales.

Crown Prosecutor – A lawyer (barrister or solicitor) who is employed by the Crown Prosecution Service. They review, prepare and prosecute criminal cases in court.

Custody – A person is in custody when they are staying in a prison or detention centre.

Defendant – A person who is accused of committing a crime.

Defending Counsel – A barrister who defends someone accused of a crime, in court.

Disclosure – The sharing of information.

Evidence – Something that proves or disproves that something did or did not happen.

Evidence-in-Chief – When a person’s own lawyer asks them questions in front of a judge and jury in court.

Expert Evidence – Specialist information relevant to a case, provided to a judge and/or jury, by a person in a particular profession. This professional offers knowledge about a topic relevant to the case, which would otherwise be unknown to the judge and jury.

Expert Witness – The person who provides information (known as ‘expert evidence’), based on their specialist knowledge, which is relevant to the decision made by a judge or jury when hearing a case in court.

Grounds – The basis for, or foundation of, an action.

Hearing – The legal proceeding which takes place in court, where the facts of a case are looked at and evidence is presented, before an outcome is decided by a judge and/or jury.

Judge – A person in charge of a trial in court. They make sure that the trial is fair, the law is followed, and sentences the defendant if they are found guilty.

Jury – Twelve people who have been chosen at random to listen to the facts of a case, sit in a trial in a law court, and to decide together whether a person is guilty or not guilty.

Lawyer – A solicitor, barrister or advocate.

Leave to Appeal – Permission to appeal.

Legal Aid – Funding provided to defendants, by the government, to help the defendant pay for lawyers and legal services, and legal assistance at the police station where someone is arrested. There is a strict eligibility criteria to receive legal aid. Information about legal aid is available at GOV.UK, and the Law Society provides information about legal aid.

Magistrate – A volunteer member of the community without legal qualification, who sits as a judge and hears cases at their local Magistrates’ court. There is usually a panel of three magistrates, who administer the law as a judge would, with the help of a qualified legal advisor.

Magistrates’ court – The court in which youth offences, less serious criminal offences, family cases (such as divorce proceedings) are usually tried. Magistrates can also hear the preliminary (first) parts of a serious criminal trial, which they send to the higher courts to be heard by a judge and jury.

Offence – A crime, or an illegal act.

Plea – The answer provided by a defendant as to whether they are ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty’. This is described as when a defendant ‘enters a plea’ of guilty or not guilty, or when a defendant ‘pleads’ guilty or not guilty.

Pro bono – This is a Latin term, which means professional work (in this case, work by a lawyer or legal professional) which is completed voluntarily and without payment, or at a lower fee. Legal charities offer pro bono advice to those who are not eligible for legal aid and cannot afford to pay a lawyer. Information about pro bono legal advice is available here.

Prosecutor – A lawyer (usually a barrister) who tries to prove the defendant is guilty of committing a crime, in court.

Public Interest – Actions must be taken ‘in the public interest’, which means with the welfare and/or safety of the general public in mind.

Remand – When a person is placed in custody (e.g. a prison or detention centre) after being charged with an offence. A person is ‘on remand‘ when they have been charged with an offence but their case is awaiting trial, unless they are granted bail.

Representation – A person is ‘represented by’ their lawyer.

Sentence – The punishment given by a judge in court, to a defendant who is found guilty. A defendant is ‘sentenced to’ a length of time in prison.

Solicitor – A lawyer who is trained to give advice and prepare cases, and can defend (or represent) people in magistrates court. The name of every solicitor in England and Wales appears on the roll of solicitors.

Solicitor Advocate – A lawyer with the same role as a solicitor, but who completed an extra qualification to be able to represent people in higher courts (e.g. the Crown Court).

Trial – The formal process which takes place in a court, when a judge and jury examine the evidence and reach a decision on the guilt of a defendant.

Unlawful – Illegal, or not compliant with social expectations.

Verdict – The conclusion made by a jury as to whether a defendant is guilty or not guilty.

Witness – A person who stands up in court to say what they saw, or know, about an event. They must first ‘take an oath’ (promise) to tell the truth.

Sources

https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/glossary

https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/en/public/for-public-visitors/resources/glossary

Civil Law – Legal Process Glossary

This glossary applies to England and Wales. The information here is based on information available on The Law Society website, and The Defendant’s Criminal Law Glossary.

Advocate – The lawyer who represents a person, or persons, in court.

Agreement – This is when both parties reach consensus on a set of facts, or a course of action.

Alternative dispute resolution – These are ways to resolve a dispute without going to court. These alternatives include arbitration and mediation.

Appeal – When a person is unhappy with a judgment and seeks to change it.

Arbitration – A way to resolve a dispute without going to court. An independent third party

(the arbitrator) looks at both sides, and decides how it should be resolved.

Assets – These are the things owned by a person or organisation that are financially

valuable.

Barrister – A lawyer who is specialised in representing people in court, drafting pleadings, and offering expert legal opinions.

Civil law – This is the area of law which covers disputes that you may have with a person or an organisation.

Claimant – The person making the claim.

Client – A person who uses the services of a lawyer or other legal professional.

Compensation – Reparations given to a claimant for harms suffered.

Counsel – Another word for barrister.

Conciliation – An alternative to the alternative dispute resolutions. This is where parties use a conciliator, who speaks to the parties both separately and together, to resolve their differences.

Damages – Compensation which is usually financial.

Grounds – The basis for, or foundation of, an action.

Hearing – The legal proceeding which takes place in court, where the facts of a case are looked at and evidence is presented, before an outcome is decided by a judge and/or jury.

Indemnity – Compensation for, or protection against, any loss or damages that might be given by one person to another within a contract or otherwise.

Interim proceedings – These are the hearings between the first hearing and the final hearing.

Lawyer – A solicitor, barrister or advocate.

Leave to Appeal – Permission to appeal.

Legal Aid – Funding provided to defendants, by the government, to help the defendant pay for lawyers and legal services, and legal assistance at the police station where someone is arrested. There is a strict eligibility criteria to receive legal aid. Information about legal aid is available at GOV.UK, and the Law Society provides information about legal aid.

Legal professional privilege (LPP) – This protection means that information shared by a client with their lawyer in confidence should not be shared by the lawyer without the client’s consent. LPP only applies between a client and their solicitor or barrister. It does not apply to other legal professionals.

Liable – This is when someone is legally responsible.

Liability – This is either: something that puts an individual or group at a disadvantage, or something that a person is responsible for.

Litigation – The dispute process that takes place in a court.

Litigant – A party involved in litigation.

Litigant in person – A person who represents themselves (instead of being represented by a barrister) in court.

Mediation – The alternative to arbitration, as an alternative dispute resolution.

Obligation – A requirement to take a particular action.

Omission – A failure to perform a particular action where there was a duty or a legal requirement.

Out-of-court settlement – When both sides settle the case privately, before the court makes its decision.

Pro bono – This is a Latin term, which means professional work (in this case, work by a lawyer or legal professional) which is completed voluntarily and without payment, or at a lower fee. Legal charities offer pro bono advice to those who are not eligible for legal aid and

cannot afford to pay a lawyer. Information about pro bono legal advice is available here.

Representation – A person is ‘represented by’ their lawyer.

Solicitor – A lawyer who is trained to give advice and prepare cases. The name of every solicitor in England and Wales appears on the roll of solicitors.

Solicitor Advocate – A lawyer with the same role as a solicitor, but who completed an extra qualification to be able to represent people in higher courts.

Tribunal – A person, or group of people, who are authorised to judge and/or determine claims

or disputes

Civil Law – Legal Process Glossary

This glossary applies to England and Wales. The information here is based on information available on The Law Society website, and The Defendant’s Criminal Law Glossary.

Advocate – The lawyer who represents a person, or persons, in court.

Agreement – This is when both parties reach consensus on a set of facts, or a course of action.

Alternative dispute resolution – These are ways to resolve a dispute without going to court. These alternatives include arbitration and mediation.

Appeal – When a person is unhappy with a judgment and seeks to change it.

Arbitration – A way to resolve a dispute without going to court. An independent third party

(the arbitrator) looks at both sides, and decides how it should be resolved.

Assets – These are the things owned by a person or organisation that are financially

valuable.

Barrister – A lawyer who is specialised in representing people in court, drafting pleadings, and offering expert legal opinions.

Civil law – This is the area of law which covers disputes that you may have with a person or an organisation.

Claimant – The person making the claim.

Client – A person who uses the services of a lawyer or other legal professional.

Compensation – Reparations given to a claimant for harms suffered.

Counsel – Another word for barrister.

Conciliation – An alternative to the alternative dispute resolutions. This is where parties use a conciliator, who speaks to the parties both separately and together, to resolve their differences.

Damages – Compensation which is usually financial.

Grounds – The basis for, or foundation of, an action.

Hearing – The legal proceeding which takes place in court, where the facts of a case are looked at and evidence is presented, before an outcome is decided by a judge and/or jury.